Columbia River Basin Watershed & Its Ecosystems

The romantic and mythic nature of the Columbia River is something that cuts across both generations and cultures. Some Native Americans call it “Nch-i-wana,” or the Big River. Lewis and Clark wrote about its beauty, power, and changing nature in their diaries. And in the 1930s, Woody Guthrie’s folk song “Roll on Columbia” reflects the awe of new settlers seeing it for the first time.

This natural beauty is distinguished by an equally rich array of natural resources. As settlers began to populate the Northwest and tap into these resources, environmental impacts became more apparent and increased over time. To better understand these impacts, this article provides an overview of key elements of Columbia River Basin ecosystems: the riparian zone, tributaries, wetlands, forests, and the estuary.

This understanding helps explain the enhancement and mitigation strategies used to address impacts to ecosystems and the plants, fish, and wildlife that call them home.

The Columbia River is much more than the water flowing between its banks. Like any river, it is ecologically inseparable from its watershed. A watershed is the land area that delivers runoff, sediment, and dissolved substances to a river and its tributaries. In turn, the health of the watershed affects the temperature, flow rate, aquatic life, and other physical components of the river.

The Columbia’s watershed spans seven states and one Canadian province. The northernmost reach of the watershed is found in the high glaciers of the Canadian Rockies. From there, the main body (or stem) of the Columbia River runs over a thousand miles before reaching the Pacific. As the river runs south and west, it is fed by many smaller rivers before it is joined by the Snake River in Pasco, Washington. Near the confluence of the Snake River the Columbia River turns sharply west, forming a natural border between Washington and Oregon. On this leg of its journey, more rivers join the Columbia before it reaches the sea.

Of the rivers that feed into the Columbia, the Snake is the largest. In fact, the streams and small rivers feeding into the Snake represent 49% of the Columbia River Basins watershed below the Canadian border.

The watershed covers nearly 260,000 square miles, an area the size of France. Abundant precipitation from the hydrologic cycle, which is described in the section “What Makes The Columbia River Basin Unique,” provides the watershed with its seasonal supply of water.

Precipitation that does not infiltrate into the ground becomes runoff, and runoff from the watershed becomes the rivers, streams, wetlands, and lakes that we care about and enjoy. Some precipitation that seeps into the ground evaporates, but gravity pulls other water deeper into the earth. Sometimes this creates an underground river. This groundwater gathers in layers of underground rock and eventually becomes an aquifer, of which there are many in the Columbia River Basin.

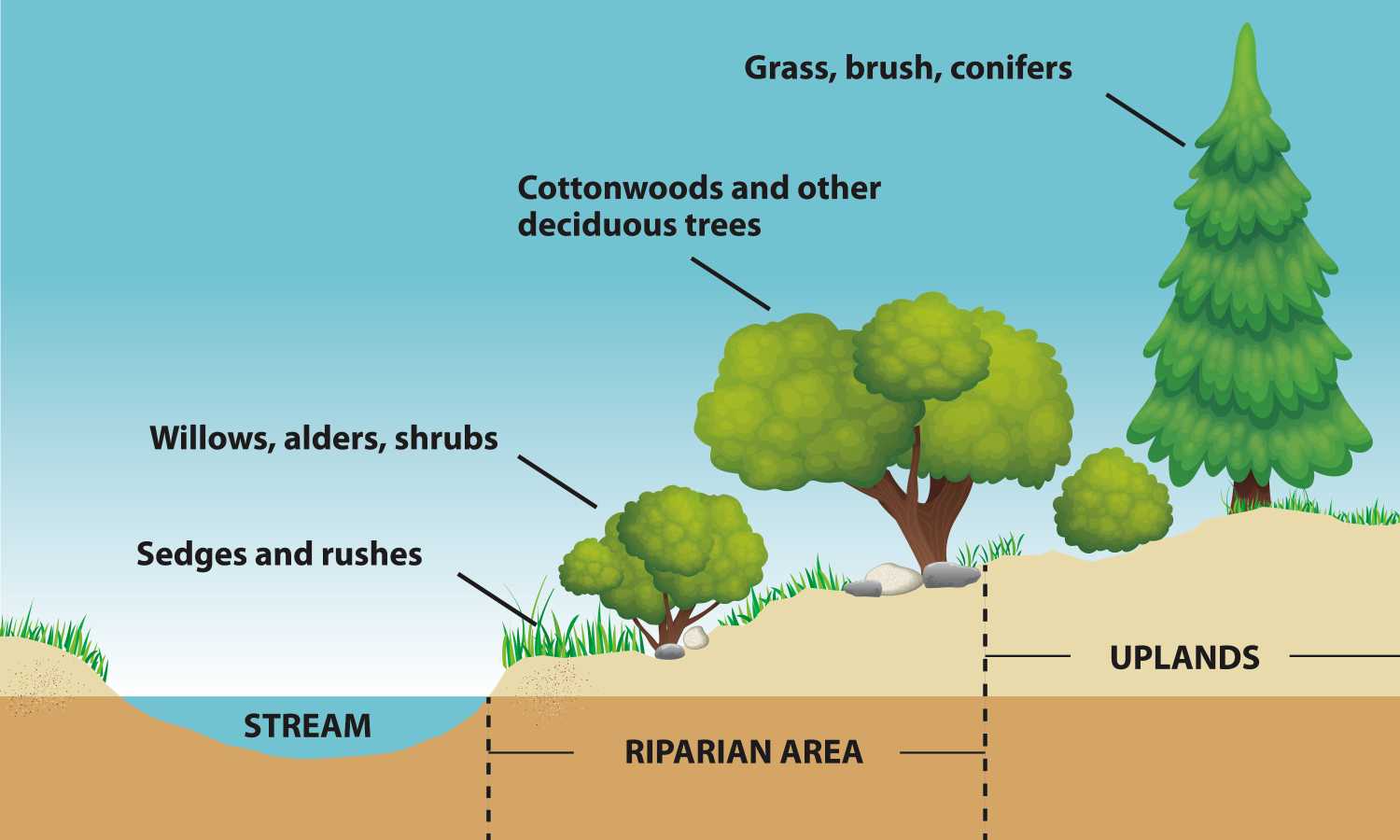

The riparian zone refers to the border of moist soils and plants that exist next to a body of water. The riparian zone can be composed of gently sloping shores, steep banks, or other types of terrain. From the perspective of a bird traveling down the Columbia, the riparian zone would change many times. These changes come about because of geologic differences, altitude, varied river flow, and the types of organisms and vegetation that can survive and thrive from area to area. As these forces interact, the nature of the river and the species which migrate to it change in concert with one another.

As the Columbia and its tributaries move downstream, the channel widens, the gradient flattens, and the water slows. In these areas more permanent plant species can survive, such as tree and shrub communities and specialized grasses and forbs (non-grasslike herbs). These plant species, in turn, provide food and shelter for the rich diversity of wildlife living along the riverbank.

Elk, deer, bear, sheep, and mountain lions are examples of animals that feed in these relatively lush riparian zones. Other smaller animals that live and feed along this biologically vital corridor include birds (like the ring-necked pheasant, grouse, geese, falcons, great blue herons, hummingbirds and warblers), small mammals (such as longtail weasel and striped skunk), reptiles (garter snake and the western painted turtle), and amphibians (red-legged frog and the Pacific giant salamander). Many threatened, endangered, or sensitive species are also frequent visitors to riparian zones. Examples include the bald eagle, peregrine falcon, and kit fox.

Riparian vegetation is also important to the health of the species that live within the river. Specifically, this vegetation helps maintain a river’s health by influencing the amount and kind of sediment in the river. Riparian vegetation does this by anchoring soil, catching silt, filtering out pollutants, and absorbing nitrogen and phosphorus. Such vegetation also helps provide shade that cools the water and provides habitat for insects and their predators.

The effect of too much sedimentation can be seen when vegetation along riverbanks is removed by flooding or another event. Sediment washes back into the water, causing turbidity. Turbidity occurs when sediment is stirred up and suspended in water, and this can impair the respiration of fish or other aquatic organisms. Turbid conditions can also cause sediment to cover gravel used for fish-spawning, raise the temperature of the water, and bury submerged plants.

A tributary is a river or stream that feeds into a larger body of water. The Snake River, originating in Yellowstone Park and joining the Columbia near Hanford, is the Columbia’s largest tributary. As water flows downstream, organic debris including decomposing organisms and leaves collect and provide nutrients to plants, fish, and wildlife.

The Columbia River’s tributaries originate in mountainous areas characterized by subalpine forest. Here, the gradient is steep and stream velocity is high. As the Columbia’s tributaries flow into the interior of the basin, pine and fir trees dominate the forest. In contrast to the higher elevations, the climate is drier, the gradient gentler, and the stream flow reduced. At the rivers mouth, forests include cedar and western hemlock. These trees thrive on heavy precipitation and a moist environment.

The Columbia’s tributaries are also strongly affected by seasonal runoff. Precipitation, primarily from winter snowfall, dramatically increases runoff from snowmelt during spring. This can cause flooding when unseasonably warm rains or winds occur.

Plants, fish, and wildlife thrive around tributaries. Many large mammals and semi-aquatic species like the playful river otter make tributaries a part of the territory they call home. Song sparrows and other small birds and mammals also live by these waters, particularly where insects are plentiful and forest cover is nearby. Fish such as the bull trout and cutthroat trout spawn in tributary headwaters, and mountain whitefish thrive in the cold, fast-moving areas of large streams.

The seven species of Pacific salmon (chinook, sockeye, coho, chum, pink, steelhead, and cutthroat trout) originate in the tributaries of the Columbia River Basin. When salmon fry emerge from their eggs, the specific tributary in which they are born is imprinted into their genetic code. They begin their descent downstream toward the ocean, allowing the current to sweep them along. When they return to the river as adults to perpetuate their life cycle, they miraculously return to the same tributary where they were hatched. For this reason, the health of tributaries is important in ensuring the genetic diversity of salmon and other migratory fish.

Interspersed throughout the watershed are wetlands. Located in lowland areas, wetlands are comprised of unique vegetation and saturated soils during all or part of the year. Once disdainfully regarded as mosquito-infested swamps, today wetlands are appreciated for serving three essential functions. These include providing critical wildlife habitat, assisting with water purification, and helping to store water during storms and floods.

Wetland vegetation is uniquely suited to life in wet soil. For instance, some trees and bushes that live in this environment have very shallow root systems. Other plant species grow roots from their stems to absorb oxygen from the air. The diverse vegetation found in wetlands may include cottonwoods and willows, rushes, cattails, and grasses. The unique conditions found in wetlands are home to many plants and species that are not commonly found.

This lush vegetation is well suited for a diversity of species. Some species are drawn to wetlands to feed and rest, others visit as part of their migratory path, and still others find wetlands to be an ideal setting for reproduction. As such, wetlands are densely and diversely populated areas. Birds such as the yellow-headed blackbird and kingfisher flit amid the sedges. Ducks and geese make wetland marshes their nesting place. And species as diverse as the high-diving osprey, the muskrat, and voles and shrews can be found there.

Beyond providing valuable wildlife habitat, wetlands also perform less noticeable functions. Wetlands along rivers and flood plains help regulate stream flow by storing water during periods of high runoff and heavy rainfall. By slowly releasing the water back into the surrounding environment, the frequency, level, and velocity of floods and riverbank erosion are reduced.

Wetlands also provide a natural water filtration process. For example, they can trap sediments and filter metals and organic pollutants like sewage and agricultural waste. This cleansed water is then released back into springs, streams, and aquifers that feed the tributaries.

Like a sponge, from the top canopy layer of a forest to its extensive root systems, water can be either absorbed, held, or released.

As water is absorbed and held by the forest, it reduces the amount of overland runoff that can lead to soil erosion. The severity of flooding, and the amount of sediment washing into rivers, lakes, and reservoirs can be regulated or reduced to some degree by healthy forests. For this reason, logging (particularly near riverbanks and lake shorelines) can have a very damaging effect.

As this map developed by the U.S. Department of Forest Service shows, only parts of the Northwest contain densely forested areas. Large parts of the Northwest are devoted to agricultural use or are characterized by shrub and scablands.

In addition, forests west of the Cascades are remarkably different from those east of the Cascades. To the west the forest is characterized by damp, foggy sea air, with a long growing season and abundant rain. Areas of deep, dark, ferny forests are the result. Western red cedar and western hemlock thrive in this climate.

As you move inland toward the lower elevations of the Cascades, thick stands of evergreens cover the mountain flanks. At the upper elevations, trees thin out as they fight to survive colder temperatures, thinning soil, and a short, cool growing season. At the higher levels of the mountains, conditions are even more severe within the subalpine forest. Alpine fir and blue spruce are examples of trees in this area.

Because the Cascades form a natural barrier to the large amounts of moisture moving east, forests on the eastern side are quite different. With much less moisture and more extreme climates, these forested areas are more sparse but extremely hardy. The ponderosa pine thrives in this climate.

In all of these forested areas, animals such as deer, bear, elk, birds, squirrels, insects, and a myriad of other species can be found. In streams and rivers, many fish rely on the shade cover of a forested area to cool the water. Also, the woody debris and leaves of trees are very important to the habitat and nutrient needs of salmon and other fish.

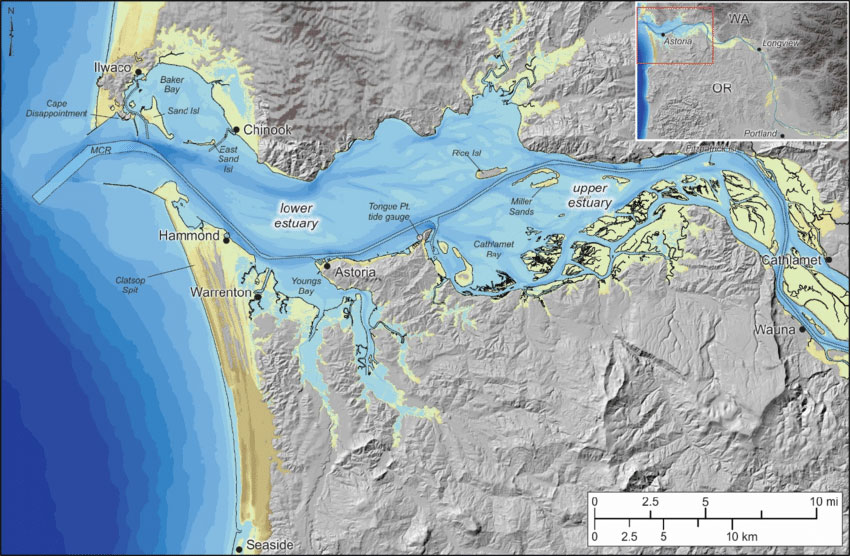

An estuary is the area where the fresh water of a river meets and mingles with the salt water of the ocean. Near the mouth of the Columbia the estuary waters have nearly the same salinity as the ocean, while upstream the salt water is extremely dilute. The Pacific Ocean’s saline influence over the Columbia River Estuary extends to a point just east of Puget Island. Within the river, the ocean’s tidal action can be measured up to the base of Bonneville Dam, which is approximately 120 river miles upstream from the mouth of the Columbia.

These dynamic conditions result in some of the most biologically productive ecosystems in the world because there is a large and concentrated supply of the nutrients from both the ocean and the river. The estuary provides important habitat for juvenile salmon as well as microscopic organisms, shellfish, mammals, and birds, including the great American bald eagle.